SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

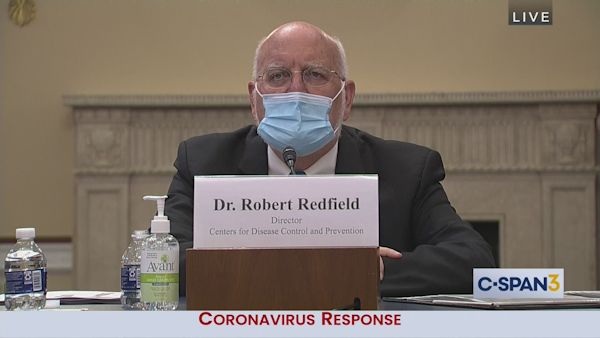

| Some say the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, widely seen in the past as a world leader on pandemic response, has been silenced during the COVID-19 outbreak. Above, a screenshot of CDC Director Robert Redfield testifying before Congress on June 4. Photo: C-Span, courtesy Google Images. Click to enlarge. |

WatchDog Opinion: Coronavirus Silence, Secrecy Harms Public Health

By Joseph A. Davis

It is urgent that the U.S. public know all the facts about the coronavirus pandemic — yet federal and state governments are often denying, hiding, muzzling and distorting information the public has a right to. It’s a case where secrecy kills.

COVID-19 is an environmental story as well as a public health disaster. Denial and nondisclosure have been familiar obstacles to environmental journalists for years. But it is even more important now that potentially fatal germs are in the very air we breathe, while pollution worsens our vulnerability.

Let’s start with the Silent CDC. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had long been regarded as an exemplar and world leader on public health and pandemic response. In the past, top CDC experts briefed the news media often and on the record during crises like, for example, the Ebola outbreak of 2014-2016.

The CDC’s objective, science-based expertise is based on experience and professional credentials. Yet many say the CDC has been “silenced.” That diminishes the health and safety of people in the United States. The CDC and other experts were used as props and puppets in the tediously long “briefings” in which President Trump got free prime airtime while he displayed his ignorance and dishonesty.

Those finally stopped, in late April, after Trump suggested that ingesting bleach might help cure the coronavirus (DON’T!). In a May 29 briefing, CDC Director Robert Redfield said the agency intended to resume regular news media briefings after a three-month hiatus.

From denial to forced recognition

Trump’s first response to the emerging pandemic was denial. In late January 2020, just after the first known case of COVID-19 on U.S. soil was identified, Trump was saying things like “we have it totally under control” and “It will all work out well.”

|

| Trump and Pence at an April 8 White House coronavirus briefing. Photo: Official White House Photo/D. Myles Cullen. Click to enlarge. |

Trump, at that time, was still facing impeachment. At a Feb. 28 political rally, Trump accused Democrats of inventing the virus concern as a political weapon, saying: “This is their new hoax.”

Many timelines of Trump’s progress from complete denial to forced recognition have been published (see accounts from NPR, The Guardian and The New York Times).

By mid-March, Trump’s tone had shifted. But he still downplayed the length of time the pandemic would last.

Later, when the White House realized it had to appear to be taking the pandemic seriously, Trump put Vice President Pence in charge of the previously quiet White House Coronavirus Task Force.

Almost immediately, on Feb. 27, the White House decreed that all agencies would clear all public communications on the virus with Pence’s office.

This naturally raised the question of whether science-based public health agencies would have their messaging filtered through political censors.

Fauci, walking a fine line

The one public health official trusted by virtually everybody was Dr. Anthony Fauci, the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who had served under six presidents and led fights against HIV-AIDS and Ebola.

The weekend after Pence took over coronavirus messaging, Fauci reportedly cancelled scheduled appearances on five Sunday talk shows. In subsequent interviews, Fauci implied that it was merely a scheduling snag and said: “I am not being muzzled.”

In his quiet, diplomatic way,

Fauci managed to offer information

at odds with Trump’s ramblings.

Although he was not fully silenced, Fauci in subsequent weeks walked a fine line between giving accurate scientific advice and falling afoul of Trump. It was rough sledding. In his quiet, diplomatic way, Fauci managed to offer information at odds with Trump’s ramblings at least nine times.

But Trump, purely out of political spite, wouldn’t let Fauci testify before the Democratic House, instead only allowing him to talk to the GOP Senate. Fauci said on May 12 that reopening the nation for business too soon could cause avoidable “suffering and death.” The next day, Trump called that statement “unacceptable.”

It wasn’t just Fauci that Trump was rejecting. It was science and public health.

By that time, however, the daily live TV performances had ceased. Fauci has since told reporters that in recent weeks his contact with Trump had “dramatically decreased.” This means Trump is getting less of the sound scientific advice that would benefit Americans.

The testing debacle

It is a given in the public health field that testing for disease is a keystone and foundation of controlling an outbreak.

Doctors in China had some ability to test for coronavirus as early as Dec. 30 (subscription required). China had mapped the genome of the virus by Jan. 2 (a key step in developing both an accurate test and a vaccine). And although Chinese authorities were initially both unsure and secretive about the outbreak, they shared the genome with the world by Jan. 12.

Based on the genome, a specific test for COVID-19 was developed, published and shared with the international community by the World Health Organization by January 20. Eventually, a COVID-19 test was developed in the United States. The approval and roll-out of the test was, by most standards, not fast enough. But just why that was and what went wrong is a complicated story.

Who’s to blame? There is plenty of it to go around. Perhaps it is a story of government snafu. But many countries outside the United States did manage to mount and implement bigger and more effective COVID-19 testing programs.

But we must note that Trump hardly welcomed the data that the tests and epidemiologists were about to deliver. On March 6, Trump said that he would rather that the 3,500 passengers on the cruise ship Grand Princess not disembark, because, “I like the numbers being where they are. I don't need to have the numbers double because of one ship that wasn't our fault."

Government responsible for testing delays

The slow pace of U.S. testing was, on several counts, the government’s fault, whether deliberate or not. The murky tale included a CDC insistence that tests must go directly through the center, a contamination of the initial batch of test kits, slow approval by the Food and Drug Administration and supply shortages.

During the long period when enough testing has been unavailable, the United States has lost ground in its fight against the virus — to the point where we have the most COVID-19 deaths in the world.

Countries like South Korea followed established public health protocols, managed to test quickly and aggressively, and ended up with very low case numbers and deaths.

Even though the WHO had a test available, the United States under Trump decided it had to develop its own. Even after the CDC said sufficient testing was a critical condition for the United States to reopen, the Trump administration pushed reopening without enough testing.

Even if the slowdown wasn’t deliberate,

there is little evidence of strong

leadership or pushing to speed it up.

Was it slow on purpose? A famous and farcical axiom called “Hanlon’s razor” states: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity."

Even if the slowdown wasn’t deliberate, there is little evidence of strong leadership or pushing to speed it up. Trump seemed to think there would be no coronavirus if there were no testing.

In a March 6 photo-op visit to the CDC, Trump declared “Anybody that wants a test can get a test.” This was demonstrably, obviously, fact-checkably untrue.

There is, in this case, strong evidence of intent to fog, fudge and fiddle the test results. In a May 11 tweet, Trump falsely claimed that COVID-19 case numbers across the United States were going down. The opposite was true. On May 7, he said, “By doing all of this testing, we make ourselves look bad.” But there’s still not enough testing.

Reopening push leads to dimming of data

As the Trump-GOP political push to reopen intensified by May, the gaslighting, disinformation and secrecy only intensified and spread.

Just for one prominent example, the experts at the CDC, following good public health principles, had drafted up several sets of guidelines for opening up various sectors of the country. These were suppressed by the politicals who controlled the coronavirus bureaucracy. They told CDC the guidelines “would never see the light of day.”

Inevitably, and quickly, the guidelines leaked. Several sets of guidelines, several times, actually.

Washington Post reporter Toluse Olorunnipa reported more such secrecy May 7 in a story headlined (may require subscription), “Trump tightens grip on coronavirus information as he pushes to restart the economy.” It included things like hiding the computer models used to predict the likely course of the outbreak and shutting down teams of experts.

Secrecy, bad information, no information, misinformation, misleading information and suppressed information — all these have been key parts for the Trump administration’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, which has so far killed more than 100,000 Americans.

They are not the basis of the sort of sound policy decisions that protect the health of Americans. They hardly fool us. Instead, they have probably deepened and worsened the harm the pandemic has done to the health, lives and livelihoods of people in the United States. But it is hard not to crash when you are flying blind.

Joseph A. Davis is a freelance writer/editor in Washington, D.C. who has been writing about the environment since 1976. He writes SEJournal Online's TipSheet, Reporter's Toolbox and Issue Backgrounder, as well as compiling SEJ's weekday news headlines service EJToday. Davis also directs SEJ's Freedom of Information Project and writes the WatchDog opinion column and WatchDog Alert.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 5, No. 23. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement